Ear Infections, Fluid and Hearing Loss

- What is an ear infection?

- Why do children get more ear infections than adults?

- Can my child catch an ear infection from another child?

- What is the difference between fluid in the ear and an ear infection?

- How do ear infections and fluid affect hearing?

- What does it mean when there is "low pressure" behind the eardrum?

- What about ear wax? Is that a problem?

- What can be done about recurrent ear infections?

- What can be done about fluid in the ear without infection?

- How does surgery help children with recurrent ear infections or persistent ear fluid?

- What are the benefits of inserting pressure equalizing tubes?

- What are the risks of inserting pressure equalizing tubes?

- Doesn't the hole in the eardrum cause a hearing loss?

- What do I need to do while the tubes are in place?

- What happens when the tubes fall out?

- Can my child swim with tubes in place?

- Can my child travel by airplane with tubes in place?

What is an ear infection?

There are several types, but in children, an "ear infection" usually means acute otitis media or AOM, a bacterial infection of the middle ear.

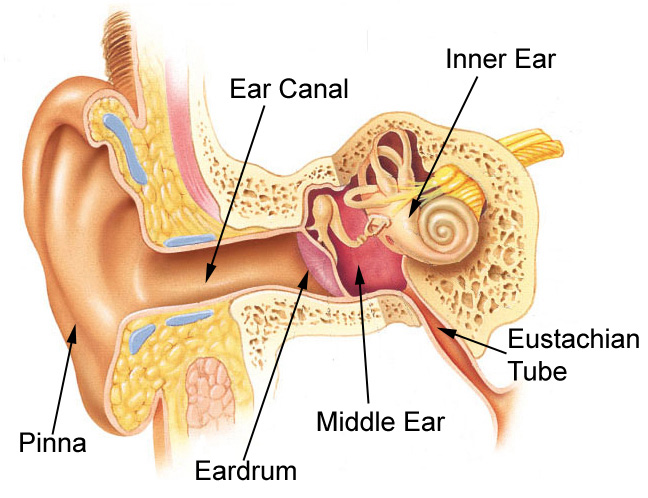

There are three main parts of the ear- the outer ear, the middle ear and the inner ear. The outer ear is just the pinna (the part that sticks out of the head) and the ear canal, which ends at the eardrum. The ear canal is where earwax accumulates. The middle ear is the normaly air filled space behind the eardrum. This space is drained and ventilated by a pathway called the Eustachian tube, which runs from the ear to the back of the nose. The inner ear is deep inside the skull, and is where the nerves and other structures controlling hearing and balance are located. It is rarely affected by childhood ear infections.

The Anatomy of the Ear

In the case of AOM, the middle ear fills up with infected fluid (pus). This can cause pain, fever, irritability and a temporary hearing loss. The diagnosis is made by seeing this infected yellow-white fluid behind the eardrum. The ear is not always red in this condition, but children with ear infections almost always have some problem hearing because the fluid interferes with vibration of the eardrum. AOM is often treated with antibiotics, although recent research suggests that in some cases, it may be ok to simply treat the pain and avoid antibiotics initially. Most ear infections resolve without antibiotics in 48 hours, but follow up is important if the symptoms persist.

The Appearance of a Middle Ear Infection

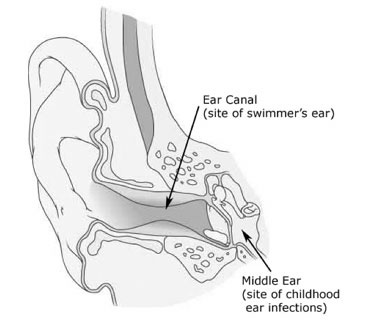

Another common condition that causes ear pain is otitis externa, or "swimmer's ear" an infection of the skin of the ear canal (outside of the eardrum). Whle this technically is an "ear infection", it is a completely different thing from AOM. The ear canal is a warm, moist place which is not easily cleaned, and a superficial skin infection can linger in this region (just like diaper rash or athlete's foot). These patients have ears which hurt when moved, and which itch severely. Otitis externa is usually treated with ear drops containing an antibiotic and possibly a steroid, but it is usually important to thoroughly clean the ear, using a microscope and suction. If you just use the drops without cleaning, they may not get in and they won't treat the infection. Cleaning is NOT something that should be done by anyone but a doctor with experience in this procedure and the right equipment. Do not try to clean the ear yourself, this may make things worse. In severe cases of otitis externa, oral (or even intravenous) antibiotics are also used, especially if the infection spreads to the outer parts of the ear.

The Appearance of Swimmer's Ear

Middle Ear Infections and Swimmer's Ear

Although otitis media and otitis externa can both be present at the same time, they generally have nothing to do with each other. In some cases, though, if there is a hole (or ear tube) in the eardrum, fluid can drain from a middle ear infection into the ear canal, causing swimmer's ear.

If there is no hole, the eardrum is watertight. Therefore, getting water in the ear canal from swimming or bathing cannot cause otitis media or any other type of middle ear fluid. While occasionally excessive water exposure can cause a swimmer's ear, this should not be confused with a middle ear infection. They are different problems and are treated differently.

Why do children get more ear infections than adults?

The main reason why children get more middle ear infections (otitis media) is poor functioning of the drainage pathway (the Eustachian tube) that connects the middle ear to the back of the nose. This tube is the body's natural way to ventilate the ear, to allow fluid to drain when the ear is infected, and to allow air to enter the ear and keep it healthy. A child's Eustachian tube does not function as well as an adult's tube for a variety of reasons. Although this is often oversimplified by saying that the child's tube is "flatter" or "narrower", there really are many differences. For example, the tube cartilage is soft and floppy, it is angled differently, and the muscles which open the tube do not work as well. The bottom line is that a young child's ears have relatively poor ventilation when compared to older children or adults.

Just as with all other aspects of human biology, there is a broad range of Eustachian tube function in children- some children get lots of ear infections, some get none. But overall, young children are more prone to ear infections and ear fluid. This tends to improve in most children by age 3-5, when the tube matures to function better.

In addition to problems with the Eustachain tube, young children have immature immune systems and may be exposed to other sick children in a school or day care setting. Upper respiratory tract infections (such as colds) are more common in children, and this can make the child's Eustachian tube function even worse, by causing swelling in the walls.

Allergies are common in children, but there is not much evidence to suggest that they are a cause of either ear infections or middle ear fluid. While allergies can and should be treated, this treatment does not seem to have much effect on ear disease. Many people assume that bottle feeding, milk products or pacifier use can contribute to ear disease, but this is controversial and it is not really clear that there is any link between these things and ear problems.

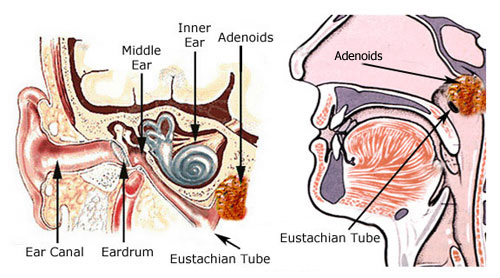

Young children do have large adenoids as compared to older children and adults. The adenoids are a pad of tissue like a tonsil in the back of the nose which can block or contaminate one end of the Eustachian tube. The adenoids are also a minor contributing factor to ear disease in children, as discussed below.

Adenoids and the Eustachian Tube

Can my child catch an ear infection from another child?

Ear infections are not contagious, but are often associated with upper respiratory tract infections (such as colds). Such an infection causes swelling in the lining of the nose and the natural drainage pathways of the ears (the Eustachian tube), which makes ear ventilation worse and makes an ear infection more likely. Also, bacteria or viruses can move from the nose to the ear through the Eustachian tube. If your child simply has an ear infection but no cold symptoms, he or she is not necessarily contagious.

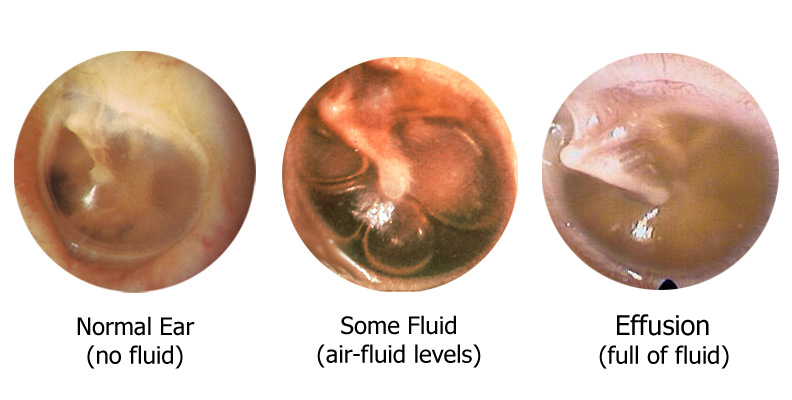

What is the difference between fluid in the ear and an ear infection?

Acute otitis media (middle ear infection) means that the space behind the eardrum - the middle ear - is full of infected fluid (pus). If there is no fluid, there is no ear infection, no matter how red the eardrum appears.

Sometimes, the fluid behind the ear is not infected, but instead is clean ("sterile"). This can happen after treating an ear infection with antibiotics, or it can occur without any previous infection. This type of fluid can be clear, yellow, thick, thin, or filled with bubbles. Clean middle ear fluid (also known as an effusion) and otits media can occur in the same child at different times. This is because the underlying cause - poor ventilation through the Eustachian tube - is the same in both conditions, not necessarily because the clean fluid is prone to becoming infected.

Middle Ear Effusion (Fluid)

How do ear infections and fluid affect hearing?

Sound reaching the eardrum is normally transmitted through a chain of 3 tiny bones in the middle ear (the ossicles). Sound waves hit the eardrum and cause vibration, which then vibrates the ossicles, which vibrate the inner ear. The inner ear turns these vibrations into electrical signals, which are then sent to the brain through the nerve of hearing. The brain interprets the electrical signals as sound. If the chain of bones and the eardrum are intact, they amplify the sound coming into the inner ear.

Fluid in the middle ear affects hearing by interfering with the normal vibration of this system. You can imagine that a drum filled with water would not make a loud sound when hit, since the water stops the drumhead from vibrating. In the same way, middle ear fluid stops the eardrum and ossicles from vibrating properly.

Middle Ear Bones (Ossicles)

What does it mean when there is "low pressure" behind the eardrum?

The poor ventilation of the middle ear by the immature Eustachian tube can cause fluid to accumulate behind the eardrum, as described above. However, sometimes the ventilation is not bad enough to cause fluid to develop, but the air pressure behind the eardrum will be lower than that in the surrounding environment. This cause the eardrum to be drawn in, or partially collapsed. While this condition is caused by the same underlying problem (poor ventilation), and can cause the transmission of sound through the ear to be less efficient (just as with ear fluid), it is a more limited problem, and usually the hearing is not that bad. In rare cases, the collapse can cause the development of a pocket in the eardrum, which can progress to other more complicated ear disease (ask your ENT doctor about this). Sometimes, low pressure is treated like ear fluid (for example, with ear tubes, as described below). However, in most cases, negative pressure does not need any treatment.

What about ear wax? Is that a problem? Should I clean it out?

Don't do this!

Ear wax (cerumen) is a normal bodily secretion, which protects the ear canal skin from infections like swimmer's ear. A small amount of it is normal, and it is not necessary (or safe) for you to try to clean out a child's ears. Using a cotton tipped applicator (such as a Q-tip®) can pack the wax deeply in the ear, or even puncture the eardrum.

Ear wax rarely causes hearing loss by itself, especially if it has not been packed in with a cotton tipped applicator. However, it may be necessary for a doctor to clean out the earwax if it is blocking the view of the eardrum. Sometimes, earwax must be removed so that a diagnosis of a middle ear infection can be made, or to help treat a swimmer's ear. In this case, it should be done by someone with the necessary tools and experience. This can be very difficult in young children who are frightened and struggling, and potentially dangerous if done wrong.

What can be done about recurrent ear infections?

Ear infections are usually treated with antibiotics. In many cases, the "milder" antibiotics (such as amoxicillin) no longer work when the bacteria become resistant to them, and "more powerful" antibiotics must be used. This is a bit of an oversimplification, as antibiotics aren't really graded by strength, but by the types of bacteria that they can treat. Although a variety of allergies can contribute to swelling in the lining of the nose and in the drainage pathway of the ear (the Eustachian tube), allergies alone have not been shown to be a major cause of ear infections or ear fluid. Therefore, allergy medications are not typically used to treat recurrent ear infections.

In the past, one approach to recurrent ear infections was prophylactic (preventative) antibiotics. This was a low dose of an antibiotic given for a longer time (1-3 months) to keep bacteria from gaining enough of a foothold in the middle ear to cause infection. This is rarely used any more, because of concerns about the bacteria becoming resistant to the antibiotics. In fact, for children over two years of age, many doctors are now avoiding antibiotics altogether, and just treating the pain initially, since ear infections usually go away on their own. This is known as "watchful waiting". If you do this, the ears should be rechecked in a few days to make sure that the ear infection has gone away.

For children who have more than 5 or 6 ear infections in a year, many ENT doctors recommend placement of ear tubes (see below) to reduce the need for antibiotics, and to prevent the temporary hearing loss and ear pain that goes along with infections. However, I less commonlyh recommend tubes in this case if the ears are clear between infections (i.e. if no fluid remains after successful treatment with antibiotics).

What can be done about fluid in the ear without infection?

A "sterile" effusion (no infection) may follow the successful treatment of an ear infection. This fluid will usually go away by itself as the body's own natural ventilation pathway (the Eustachian tube) gradually drains the ear. In other cases, the fluid may be present for many months without any history of infection.

There is no good evidence that any medical therapy helps the middle ear fluid to drain. In the past, children with ear fluid were often treated with antibiotics, decongestants, nasal steroids or antihistamines. Since these have not been shown to help, and since they may have harmful side effects, I do not recommend any of these for ear fluid alone.

One apporach that can occasionally clear the fluid in chilren that are not too young (over age 3) is the use of an Otovent device. This is basically a small balloon connected to a plastic holdler that lets children blow up the balloon with their noses! It causes them to do the internal maneuver that you might do when blowing your nose or clearing your ears on an airplane or when diving underwater. Young chidren may have a hard time doing this on their own, and this devices helps them learn how to do it. We have them in my office

For children who have persistent middle ear fluid for more than a few months, ENT doctors will often recommend ear tubes (see below). This is especially helpful in cases where the hearing loss is contributing to speech or learning problems, or in cases where there are other underlying problems such as developmental delays.

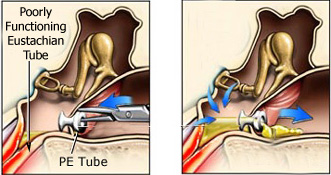

How does surgery help children with recurrent ear infections or persistent ear fluid?

Some children may be offered surgery for these problems, placing a small drain through the eardrum. This operation is known as BMT, for Bilateral (both sides) Myringotomy (the hole in the eardrum) and Tubes (the drain placed through the hole). The tubes themselves are known as pressure equalizing tubes (PET). Although there are a lot of things that go into the decision to operate, BMT is typically recommended after the fluid has been present with hearing loss for several months, or occasionallly for a child who has had 5-6 ear infections in the previous year.

PE Tube Bypassing the Eustachian Tube

It is important to remember that the tube does not "fix" the underlying problem (immature Eustachian tube function and poor ear ventilation). This problem almost always goes away on its own with growth and development. While some children take longer to grow out of ear disease than others, very few children still have this problem past age 6. The tubes simply act as a "crutch", bypassing the problem by ventilating the ears through the eardrum, so that the chance of ear infections is minimized, and ear fluid accumulation is prevented, while waiting for improvement with growth. By the time that the tubes come out, most children have grown enough to ventilate their ears on their own - although a small percentage may need to have them placed more than once. Children who have a cleft palate often have very prolonged dysfunction of the Eustachian tube, requiring tubes for many years.

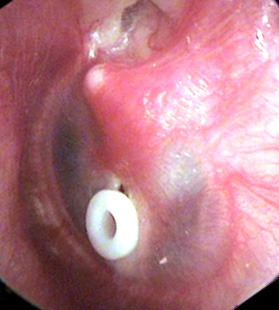

Short Acting PE Tubes

Long acting tubes are used with children suspected of having severe, long-term Eustachian tube problems. Such problems may be seen in children with cleft palate, Down syndrome, various head and neck syndromes, or older children who have had longstanding ear problems and collapse of the eardrum. While the long-term tubes make replacement surgery less likely, they have a greater chance of leaving a persistent hole in the eardrum after they fall out or are removed, which would then require more surgery to repair. For this reason, I prefer short acting tubes in most cases.

PE Tube in place in the eardrum

Some surgeons recommend shaving down the adenoids at the same time that tubes are placed (it is not possible to remove them completely, it is always a shaving operation, no matter who does it). The logic behind this practice is that the adenoids sit at one end of the Eustachian tube (in the back of the nose), and may contribute to ear infections and fluid. It is not totally clear why the adenoids have this effect. One theory is that they physically block the Eustachian tube, interfering with its function. Another theory is that they provide a place for bacteria to grow which then inflame the Eustachian tube, or travel up the tube into the ear.

Adenoidectomy adds a small amount of time and risk to the surgery, and like all operations, should not be done unless there is a good reason. I generally recommend adenoidectomy at the same time as tube placement only if the adenoids are large and causing significant blockage of the nose (such as sleep apnea), or occasionaly with the second set of tubes. However, each child is different, and there are a many factors which contribute to the decision to shave the adenoids.

What are the benefits of inserting pressure equalizing tubes?

In children who have persistent ear fluid, the benefit is usually seen immediately. Once the fluid is suctioned from the ear, hearing starts to improve, although it may take a few days for all of the fluid and blood to drain from the middle ear, so I usually wait a few weeks before repeating the hearing test. Many parents of children with speech delay related to hearing loss will report a quick improvement in language and socialization after surgery. The ventilation that the tube provides prevents the fluid from coming back, as long as the tube is functioning (i.e. not clogged with wax or other debris).

For children with recurrent ear infections, they allow for drainage, and may reduce the need for oral antibiotics. However, it is still possible to get an ear infection, especially during a cold. In this case, though, the ventilation tube serves to drain the infected fluid out of the ear. Therefore, the child experiences less pain and fever than they would if the tubes were not in place, and oral antibiotics are rarely needed.

What are the risks of inserting pressure equalizing tubes?

The most common problem after tube placement is persistent drainage of liquid from the ear. Although the tube is placed to allow for drainage as well as ventilation, sometimes the drainage continues for weeks and may cause symptoms such as itching or a foul odor. In this case, it may require specific treatment. The ear is suctioned in the office using a microscope to keep the tube from getting clogged and to keep the drainage from infecting the skin of the ear canal ("swimmer's ear"). Also, a medicated ear drop may be perscribed to help fight the infection. It is important not to use these drops for too long, so be sure to ask you doctor about when they should be stopped. Occasionally, an oral antibiotic may be added to help the infection clear up more quickly, especially if the drainage lasts for more than a few weeks.

In rare cases, the hole in the eardrum will not close as expected after the tube comes out (persistent perforation). This is very uncommon with short acting tubes, but the chance goes up the longer the tube stays in place. Therefore, I recommend that no tube stay in for more than two years. Long acting tubes are made of soft material, and can be easily removed from the eardrum in the office without much pain. Occasionally, a short acting tube will not come out on its own in two years. Since these tubes are hard plastic, it would be painful to remove them from the eardrum in the office and so it is done under a brief anesthetic. I usually take the opportunity to freshen the edges of the tube site and put packing material over the eardrum to help it heal.

Many parents are concerned about "scarring" of the eardrum. This refers to the fact that an old tube site can sometimes be seen after tube placement. In most cases, scar tissue on the eardrum does not cause any problem at all, and hearing is generally normal once the fluid is gone. Serious injury to the middle or inner ear mechanism during surgery is extremely uncommon.

The surgery to insert tubes is done under general anesthesia. This is usually the most frightening part of the whole process, for children and for parents. However, it is extremely safe. While the operation only takes a few minutes, it is vital that the child be absolutely still, as even a small amount of movement could cause permanent injury. Although tubes can be placed in adults with local anesthesia, it is simply not possible to do this safely in most younger patients. Click here for a more thorough discussion of anesthesia in children.

Doesn't the hole in the eardrum cause a hearing loss?

No, the hole actually improves the hearing by draining fluid. The size of the hole is so small compared to the overall size of the ear, that it does not significantly reduce the surface of the eardrum. Even with a tube in place, the drum vibrates well enough for normal hearing to occur.

What do I have to do after the tubes are placed?

In general, tubes do not require much attention.

I see my patients with tubes around 3 weeks after surgery, and then every three months until the tubes fall out and the ears are fully healed and healthy. I repeat the hearing test (the audiogram) at the time of follow up visits, to monitor the hearing. I do not require any special ear protection with surface swimming or bathing in most children (see below).

If a child has a draining ear for more than 3-4 days, I ask that he or she be brought into the office for an examination. The ear canal is suctioned clean using a microscope, to prevent the tube from becoming clogged and to avoid irritation of the ear canal skin. In some case, ear drops are recommended. Occaisonally, a little bit of earwax or dried blood can block the tube, making it non-functional. This can also usually be dealt with by special ear drops.

What happens when the tubes fall out?

The tube is pushed out as the eardrum grows. As this happens, the tube is designed to fall outward, into the ear canal. Once it is there, it does not cause any harm and may be removed in the office painlessly at any convenient time. Sometimes, afer several months, it can work its way out of the canal and fall out of the ear entirely.

Once the tube is out and the hole in the eardrum has closed, the child is once again dependant on his or her own natural ear ventilation to prevent ear infections and the accumulation of fluid. Tubes are placed to "buy time" and allow for ventilation while the child's ears mature; ideally, by the time the tubes are out, the child has outgrown the ear problem that required the operation. However, this is not always the case.

About 10-15% of children will need a second set of tubes, and a smaller number will need a third set. Such children may have underlying problems which make them take a long time to grow out of their ear disease (such as cleft palate), while others are otherwise normal but just take longer to develop good Eustachian tube function. Long acting tubes make the chances of a second operation less likely, but this must be balanced against the greater possibility of persistant perforation (especially if they are not removed after two years). In each child, a number of factors go into the decision as to what type of tubes to place and whether or not they need replacement.

Can my child swim with tubes in place?

The reason that water precautions were recommended was to prevent water from flowing into the ear through the tube, causing infection and drainage. However, it seems that the pressure required to force water through the tiny tube is not reached unless the child's head is at least a foot or so under water. Even then, there is no clear evidence that water will be pushed into the ear during swimming. Furthermore, the rate of infection has been found to be about the same whether children swim with protection (earplugs), swim without protection, or don't swim at all. Bathing also is unlikely to result in water entering the ear through the tube in most cases.

While research has not been done on all possible water exposure situations (such as lake water) here are some general guidelines for water protection with tubes in place:

- Children swimming in a chlorinated pool near the surface do not need to wear ear protection at all (even if they put their faces into the water). In any case, most children who have tubes placed are fairly young, and do not dive deep under water.

- Normal bathing or showering does not require ear protection. A shower spray should not be directed into the ear canal, and prolonged soaking with the ears under soapy bathwater should be avoided.

- Children with recurrent ear drainage after water exposure should wear ear protection, and should be seen by the surgeon to make sure that the tubes do not become clogged with debris.

- Children who have ear tubes in place and who swim more than a foot or so under water should wear ear plugs.

- Deep diving (more than 3-4 feet underwater) should not be done even with ear plugs while pressure equalizing tubes are in place.

Can my child travel by airplane with tubes in place?

Yes, and air travel can take place immediately. One of the additional advantages of tube placement is that the ear pain of takeoff and landing will be eliminated. This pain is caused by the ear's inability to rapidly equalize air pressure between the pressure level in the cabin and the pressure level behind the ear drum. With tubes in place, the pressure equalizes instantly, and no pain should be felt unless the tube has become clogged.